Today, we’re going to have a little bit of fun. We’re going to talk about English. What is it?

Today, we’re going to have a little bit of fun. We’re going to talk about English. What is it?

According to WIkipedia, “English is a West Germanic language in the Indo-European language family, whose speakers, called Anglophones, originated in early medieval England on the island of Great Britain.” That’s technically correct, which is the best kind of correct.* In reality, English is a linguistic mob led by a medieval form of Germanic that lurks in dark alleys waiting to mug other languages to steal words, phrases, and even sentence structures, leaving the victim language bewildered and afraid. (Sidenote: I don’t think Japanese is scared of any other language, but Klingon tends to keep the bat’letlh sheathed ‘cuz it don’t want no trouble.)

So why is English such a mishmash of rules, words, and idioms that have no relation to each other? Why is the “k” in “knife” silent? (Blame the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes.) Why so much Latin and French in the language? (Blame the Normans.) And why does “-ough” have too many ways to pronounce it? (Blame Gutenerg and Tyndale.) And how in the hell did we end up with a Latin alphabet of 26 letters when English has a minimum of 42 sounds. (48 if you use the Shavian alphabet. I’m actually not opposed to that idea, except you’d have to learn to read all over again.)

First, where did English come from? Well, as the quote above says, it’s a West Germanic language. It came from Germany shortly before the Roman Empire withdrew from Britain. Prior to that, the inhabitants spoke Latin, Celt, and a few other languages. But the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes didn’t so much invade Britain as they landed there over time and decided they liked the place. A few Romans stuck around, and so the new dominant culture, a mix of those same Angles, Saxons, and Jutes, began speaking their common tongue. In a foreshadowing of the future, this new language promptly raided Latin for a handful of constructions. (No, that does not prove the Latin nerds right about prepositions and split infinitives.) While the Jutes were basically ancestors of the Vikings (from Jutland in Denmark), they adopted the evolving Germanic of these Angles and Saxons, later dubbed “Anglo-Saxon.” We still speak a lot of Anglo-Saxon today, but the actual Anglo-Saxon would be unrecognizable both in writing and spoken aloud. It’s the basis of the modern English language, hence we call it “Old English.” Only, it sounds like Dutch.

Anglo-Saxon gave us Beowulf, an epic poem that actually came from the Vikings. Originally, they wrote in runes, but the conversion of the British Isles to Christianity prompted them to adopt the Roman alphabet, keeping some runes to denote certain sounds. For instance, the letter “y” has a slightly different counterpart to the voiced “th” sound that was still used up until Shakespeare’s time. Shakespeare and the King James Bible are actually written in modern English. Parts of Yorkshire and Appalachia have kept a lot of this dialect, which falls under the “Elizabethan” banner. But if you want to know why your favorite Renaissance fair has a lot of shops that say “Ye Olde Smithy” or “Ye Olde Turkey Leg Shoppe,” the “Ye” is not the plural ye Jesus used with his pals in the KJV. It’s actually “the.” And that “y” looks different from the one in “yes.” (My favorite Thes album is Close to ye Edge, but I have a soft spot for Drama and 90125. See how silly that mistake sounds?)

Then came the Vikings. Like other languages (including the Old Norse of the Vikings), early English gendered and pluraled their definite articles. If you know Spanish or French, you’ve seen four definite articles–el, los, la, and las in Spanish, for instance. Like most Germanic languages, this got confusing once the Norse settled down and became rivals to the Saxons and overlords of the Angles. (Hence, “England.” Land of the Angles. Saxony was already taken.) They convinced their Anglish and Saxon in-laws to simplify things by just saying “the” without regard to gender or singular vs. plural. In fact, English no longer genders its nouns, not even neuter. They’re just nouns.

Where things get hairy is the Norman Conquest. After bending French to their will by creating their own dialect, these Viking-descended French proceeded to remake the English language in its own image. So half our words come from French. Not content with that, Willy the C’s grandson, Henry II, had a father named Geoffrey Plantagenet, who was a traditional Frank. So now another version of French came ashore, further muddying the waters. Then King John lost all of Normandy except for two islands (the Channel Islands), English began to drift back into mainstream. But it wasn’t the Anglo-Saxon of Alfred the Great or Canute. This was Middle English. The best example of this version of English is The Canterbury Tales, by John LeGaunt’s (progenitor of the current royal family) BFF, Geoffrey Chaucer. If you read Canterbury Tales in its original form (with modern letters used), you can make some sense of it, or get a bad headache trying. Spoken, it sounds like heavily accented modern English. By this point, English had inherited the pillaging ways of the Vikings, who added to Anglo-Saxon and began raiding Latin, the neighboring Celt languages, and even Dutch and German for words. Another funny thing happened on the way to Shakespeare: Vowel drift.

It was around this time that -ough started to take on as many pronunciations as possible. In Chaucer’s time, it was pronounced like “cough,” only with a soft K sound at the end instead of an H or silent. So you would plugh your field, but if you did it in the rain without a coat, you would catch a cogh, and that might be rogh. According to language nerd Rob Watts, whose RobWords YouTube channel I’m now addicted to, the ough sound, represented by a letter that looked something like a stylized 3, began to change when the Black Death abated in London. (Ironically, so did the Wars of the Roses and the Hundred Years War.) People speaking different dialects drifted toward the major cities like York and London seeking higher wages because, well, death creates labor shortages. Also, people from other countries came to England seeking higher wages because, well, death creates labor shortages. But that letter might have preserved a uniform -ough sound. Then Gutenberg had to create his printing press with a Roman-only alphabet.

Mind you, Gutenberg was German and only had to replace one letter and maybe slip in an umlaut or two. IT workers (like me) of a certain age can remember a similar problem when computers did not all run ANSI or, later, Unicode, which have robust symbol libraries. No, we had ASCII, which made for some interesting text-based artwork, but made formatting a pain in the broc. (Anglo-Saxon for ass.)

By the time of Shakespeare, English had evolved into modern English, what we speak today.

“Wait a minute. What about ‘How now?’ and ‘Thee’ and ‘Thou'”?

I said it was modern English. I also said the dialect, commonly called Elizabethan, is only spoken in a few places now. The rules we know were pretty much solidified in this era. You can thank William Shakespeare. And John Milton (a Shakespeare uber-nerd.) And King James I of England (or King James VI of Scotland. They wouldn’t unite the thrones for another 2 centuries, just in time to import kings from Germany.) People notice the second-person pronouns more than anything else. This is because English still had formal and informal “you.” Your friends and neighbors are thee/thou, using thy or thine to show possession. The formal “you” also had “ye” (not to be confused with Anglo-Saxon “the” because… Reasons.) As Britain, and subsequently America and Canada, moved away from the Catholic Church and even the Church of England, it also moved away from formality in the language. It just became easier to say you and yours. If you live in the American South, “y’all” is acceptable (as are the Yinzer “youins” and East Coast “youse”) for a plural of you. Some people even believe thee and thou are formal. Why? Well, the only place they see it is in the Bible. Just not in any translation since 1700.

The language is still evolving. Technology has accelerated verbing a brand name. We Xerox, even though Xerox is not the most common copier or printer anymore. Even in Bing and Duck Duck Go, we Google. And try as we might, those of us who have fled X, and quite a few who stayed behind, still “tweet.” Additionally, before it become a political hot potato, the language already began to accept “they” as gender neutral third person. Why? Calling someone “it” just makes you sound like a douchenozzle. (That is actually in at least one dictionary, and as both a hygiene device and an unlikeable person.) I ignore the political rancor over singular “they” because it lets me spike the football on my tenth-grade English teacher’s grave. That’s right. Suck it, Clara!

Ahem! I mean, sorry, Mrs. S.

*No, it’s not.

Back in the old days, when my dad would take us all out in his LaSalle to the five-and-dime for a grape Nehi while Rudy Vallee warbled “Whole Lotta Love”… Um… Wait. They didn’t make LaSalles when my dad was born, Rudy Vallee had given way to big bands, and my earliest memory of a new song was “Something” by the Beatles when I still had not known the horror of kindergarten. Let’s start again. Back in high school, before the age of word processors, cloud storage, and AI, we were taught to write in drafts. In fact, my favorite English teacher Mr. Murphy (still going strong at 90!) told us to write out the first draft by hand before sending it across the typewriter. Subsequent drafts, after chopping up with a red pen*, were to fix flow, spelling, typing, etc. If the truth be known, I was 30 before I could type, and by then, word processors and computers were a thing.

Back in the old days, when my dad would take us all out in his LaSalle to the five-and-dime for a grape Nehi while Rudy Vallee warbled “Whole Lotta Love”… Um… Wait. They didn’t make LaSalles when my dad was born, Rudy Vallee had given way to big bands, and my earliest memory of a new song was “Something” by the Beatles when I still had not known the horror of kindergarten. Let’s start again. Back in high school, before the age of word processors, cloud storage, and AI, we were taught to write in drafts. In fact, my favorite English teacher Mr. Murphy (still going strong at 90!) told us to write out the first draft by hand before sending it across the typewriter. Subsequent drafts, after chopping up with a red pen*, were to fix flow, spelling, typing, etc. If the truth be known, I was 30 before I could type, and by then, word processors and computers were a thing.

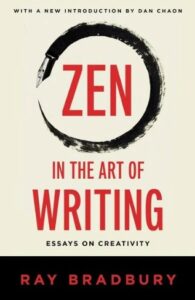

Ray Bradbury wrote a book about it. He came up in the age of pulps. His best known science fiction novel,

Ray Bradbury wrote a book about it. He came up in the age of pulps. His best known science fiction novel,  Writers get a lot of inspiration from music. From other writers. From poetry. It’s only natural they would want to quote it.

Writers get a lot of inspiration from music. From other writers. From poetry. It’s only natural they would want to quote it. Publishers, especially those in small press, are traumatized by how too many manuscripts come in. Goofy fonts. Weird margins. Author never read the guidelines. (Pro tip: If you’re asking someone to sell your work for you, they make the rules on formatting. End of discussion.) But it gets witchy for editors, too. However, I get it. Writers have so much anxiety about query letters (Maybe agents need to quit talking so much about that. All they do is induce performance anxiety.), acceptance and rejection, and getting seen! And if it’s a first-time novelist, and you’re the lucky editor who gets to read them, you’re reading someone’s baby!

Publishers, especially those in small press, are traumatized by how too many manuscripts come in. Goofy fonts. Weird margins. Author never read the guidelines. (Pro tip: If you’re asking someone to sell your work for you, they make the rules on formatting. End of discussion.) But it gets witchy for editors, too. However, I get it. Writers have so much anxiety about query letters (Maybe agents need to quit talking so much about that. All they do is induce performance anxiety.), acceptance and rejection, and getting seen! And if it’s a first-time novelist, and you’re the lucky editor who gets to read them, you’re reading someone’s baby! arks, which is a challenge. Em dashes (or for the more pedantic, dialog dashes. Hate to burst your bubble, nitpickers, but the readers who pick up on this don’t care. Neither do I.) are generally used in Romance languages like Spanish, Italian, or French. I’m not sure why writers in English–any dialect of English–choose to do this, but then Cormac McCarthy dispensed with quotation punctuation altogether.

arks, which is a challenge. Em dashes (or for the more pedantic, dialog dashes. Hate to burst your bubble, nitpickers, but the readers who pick up on this don’t care. Neither do I.) are generally used in Romance languages like Spanish, Italian, or French. I’m not sure why writers in English–any dialect of English–choose to do this, but then Cormac McCarthy dispensed with quotation punctuation altogether. The Elements of Style

The Elements of Style

Writing the Novel

Writing the Novel  On Writing

On Writing Save the Cat

Save the Cat Apologies to Steve Perry

Apologies to Steve Perry It’s no secret I have a love-hate relationship with my first novel. Published as James R. Winter (later shortened to “Jim Winter” because the former sounded pretentious),

It’s no secret I have a love-hate relationship with my first novel. Published as James R. Winter (later shortened to “Jim Winter” because the former sounded pretentious),  Today, we’re going to have a little bit of fun. We’re going to talk about English. What is it?

Today, we’re going to have a little bit of fun. We’re going to talk about English. What is it?