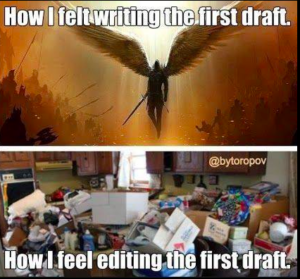

The bulk of what I edit comes from a publisher. So it stands to reason each writer, regardless of flaws, knows how to write. Now, how well they write is up for some debate, and that includes your humble narrator. Self editing, of course, is a tricky skill to master. It’s why I’m a fan of Stephen King’s process, where in the rough draft gets shoved into a drawer or dark corner of the cloud for two or three or six months. That masterpiece you wrote in the heat of the moment suddenly looks like the literary equivalent of a Very Special Episode of Hoarders.

But you should know how to write, even in that messy, everything-but-the-kitchen-sink first version of the story you’re writing. I mentioned on my author Substack that I just started a short story I knew was already bloated because it takes too long to wade in. Of course, I’m GenX. Typewriters and dedicated word processing machines were still a thing when I began to work on my craft. I know one Gen Z writer who says he doesn’t do drafts. He just revises the existing original. He’s about fifteen years younger than me and started writing probably on Word Perfect or even the early Microsoft Word. Which means we’re both old enough to have owned cassettes for music and don’t cotton to these fancy, newfangled apps like Scrivener. (Scrivener has been around long enough to cultivate quite a few “Get off my lawn!” types among its fan base. Welcome to the geezers club, Scrivenites. The guys still using IBM Selectrics will be tending bar this evening.)

“Well, gee, Hottle. Are you going to get to your point?”

Now that the bush has been thoroughly beat around, yes.

This column, and dozens of others just like it, are about beating a manuscript into submission. (For submission, though no pun was intended.) Some time back in the 2010s, all the writing advice became about flogging books on Kindle, how to crank out 10,000 words while walking your dog, taking a shower, or getting a root canal. (Pro tip: Dragon Anywhere does not understand WTF you’re saying when a dentist is ripping bone out of your mouth.) None of it was about the joy of writing, why we do it, what drives us to sit at the keyboard and make stuff up.

Ray Bradbury wrote a book about it. He came up in the age of pulps. His best known science fiction novel, The Martian Chronicles, was welded together in outline form almost on a dare from his editor (who wrote him a check the next morning.) Bradbury knew he wanted to write from earliest childhood. I’ve heard tell of writers whose parents discouraged them. One gent I used to know took beatings over it. (He’s old enough to be my father, so put that into generational context. My dad transitioned from spanking to the time-out because the latter really pissed off my brother. I digress. Again.) No, Bradbury collected memories. He wrote down lists of nouns that triggered those memories. And he talks to his characters. He actually will chat with them, listen to them. It’s how he adapted Fahrenheit 451 and Something Wicked This Way Comes for stage and screen. And I’ve noticed movies based on Bradbury’s work tend to hew more closely to the original source than that of other writers. Stephen King comes close, even when a director “has their own vision” (Shut up, Stuart Baird!), though the director of The Outsider needs to apologize for trying to excise Holly Gibney from that story.

Ray Bradbury wrote a book about it. He came up in the age of pulps. His best known science fiction novel, The Martian Chronicles, was welded together in outline form almost on a dare from his editor (who wrote him a check the next morning.) Bradbury knew he wanted to write from earliest childhood. I’ve heard tell of writers whose parents discouraged them. One gent I used to know took beatings over it. (He’s old enough to be my father, so put that into generational context. My dad transitioned from spanking to the time-out because the latter really pissed off my brother. I digress. Again.) No, Bradbury collected memories. He wrote down lists of nouns that triggered those memories. And he talks to his characters. He actually will chat with them, listen to them. It’s how he adapted Fahrenheit 451 and Something Wicked This Way Comes for stage and screen. And I’ve noticed movies based on Bradbury’s work tend to hew more closely to the original source than that of other writers. Stephen King comes close, even when a director “has their own vision” (Shut up, Stuart Baird!), though the director of The Outsider needs to apologize for trying to excise Holly Gibney from that story.

Bradbury approaches life as one long journal entry. Something happens to him or around him, and he knows an idea from it won’t emerge for years, sometimes decades. It’s obvious to anyone who’s read Something Wicked This Way Comes. And if you read between the lines, you can see an homage to Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio in The Martian Chronicles. And, I suspect, shades of Stephen King’s Castle Rock, too.

There is actually no Zen in Zen in the Art of Writing. Well, not until the end, with the essay that gives the book the title. This is Ray Bradbury telling you he’s not a science fiction or literary god but just a kid from Waukegan, Illinois, who got to make stuff up for a living. One suspects he’d have done it whether he got published or not. Writing is, after all, an unstoppable madness for many. Including Bradbury.

The Elements of Style

The Elements of Style

Writing the Novel

Writing the Novel  On Writing

On Writing Save the Cat

Save the Cat